According to data from the Santiago de Compostela Tourist Office, almost 263,000 pilgrims come to the city each year (in jubilee years, that number doubles to half a million). Of these, half are foreigners from across all continents. 85% are European, half of whom are Spanish, from every region, but mainly from Madrid, Andalusia and Catalonia. More than 90% go on foot, with the rest going by bicycle (9.6%, around 25,000 people), on horseback (326 people), and a small number in wheelchairs (71 in 2015). They all get their “compostela” or accreditation, for reaching their goal, which is issued by the Pilgrim’s Office. To get their certificate, pilgrims must travel the last 100 kilometres on foot or horse, or 200 kilometres by bike, and prove their achievement with the stamps that they receive for each stage, the only requirements needed to consider their journey complete.

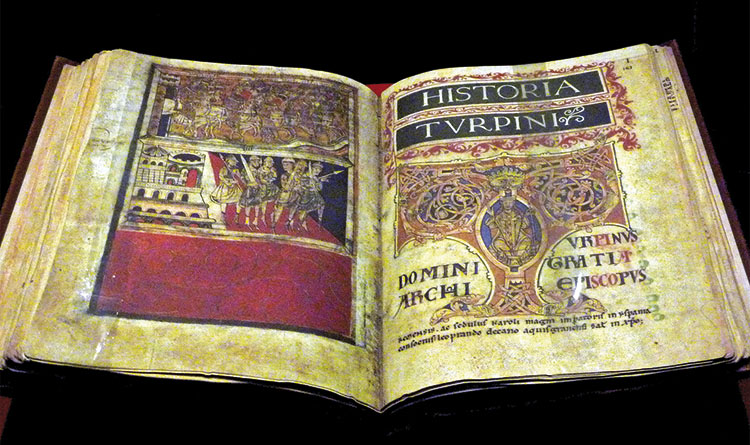

This journey started in the Middle Ages, when the remains of St. James the Greater were discovered in the 9th century near the city. According to history and legend, this follower of Jesus preached in the land that we now know as Spain –a fact highlighted by scholars such as Beatus de Liébana– and then subsequently travelled to Palestine, where he was martyred, with his remains finally arriving in Galicia at the campus stellae, or field of the stars –whose name comes from the mysterious lights that attracted its discoverers– which, it is believed, gave ‘Compostela’ its name. When the Muslims invaded the peninsula, with the exception of the Kingdom of Asturias, the devotion to the Apostle quickly grew, and he was soon considered the patron saint of Spain.

Together with Rome and Jerusalem, Santiago became a great centre of Christian spirituality. The rise of pilgrimages, journeys with a sense of penance, the atonement for sin, fit with the medieval mindset in which spirituality was present in all areas of daily life. This was also in line with the concept of homo viator, human beings as “pilgrims” in earthly life, in transition to a spiritual and internal life that can only be attained by the cleansing of sin. So much so that forcing prisoners and criminals to go on the Camino de Santiago became a standard sentence in some European courts of the Middle Ages, although the pilgrimage was made by people of all social classes, including nobles, some of whom commissioned others to walk the route on their behalf.

These days the profile of the travellers is much more varied, and ranges from true pilgrims who more than anything are seeking an inner experience, to tourists, adventurers, and curious types, as well as every other possible combination. As a result, although participation in the Camino is free, there are many companies that offer all kinds of services –transport and storage of backpacks, suitcases and bicycles– and tourist packages that, in addition to walking sections, also include guided tours, airport, bus or train transfers, riding on horseback and even donkeys, hotels, gastronomy, etc.

And as was the case centuries ago, the Camino itself is an economic engine and cultural itinerary of the highest order, offering boundless artistic and natural riches. Although, in many cases, the routes leading to Santiago already existed before the discovery of the tomb of the Apostle, they prompted the entry and dissemination of cultural currents from the rest of Europe. After reaching its peak in the 12th and 13th centuries, the Camino went into decline, and it was not until the 1980’s that it started to regain its value, going on to become the huge phenomenon that it is today.

While the “French Route”, which crosses the Pyrenees through Roncesvalles, is the most popular route to reach Compostela from Europe, chosen by more than 66% of the pilgrims, there are more than a dozen routes throughout Spain. Virtually every region has its Jacobean route, many of which were forgotten and have been rediscovered thanks to the work of associations and scholars. In 2015, UNESCO expanded its ‘Heritage of Humanity’ classification, which the French Route had held since 1993, to include four other routes to the north of the country: the Coastal Route; the Inland Route of the Basque Country and La Rioja; the Liébana Route and the Camino Primitivo, which together total 1,500 kilometres.

At the same time, Spanish associations of friends on the Camino de Santiago –34 in total–, have studied, revived, and marked 12,000 kilometres of routes with yellow arrows, throughout Spain since the late 1980s, in addition to recruiting 700 volunteers known as “hospitaleros”, to work in around 40 free hostels, which were referred to in the past as “hospitales”. The pilgrims also have a further 400 places of paid accommodation managed by parishes, municipalities and other entities and institutions.

Pilgrims tracks

- Romanesque and Gothic cathedrals: such the one in Santiago -a Romanesque jewel with the spectacular Pórtico de la Gloria and the Baroque Fachada del Obradoiro-, Jaca, León, Burgos, Palencia, Oviedo and Lugo.

- Churches: such as the Santa María de Eunate church (Navarra), an architectural rarity with an octagonal floor and connections to the Order of the Templars, or the Virgen Blanca Church (Palencia). The oldest churches are the Asturian Pre-Romanesque churches of San Miguel de Lillo and Santa María del Naranco.

- Monasteries: like the San Juan de la Peña monastery (Huesca), half-excavated into the rock in a spectacular natural location; and San Juan de Ortega (Burgos), where twice a year the phenomenon of equinoctial light (a ray of light that illuminates a Romanesque capital) takes place, and which can also be seen in the Santa María de Tera church in Zamora. Other important monasteries are Santo Domingo de la Calzada and San Millán de la Cogolla (La Rioja), Leyre (Navarra), etc.

- Bridges: Trinidad Bridge (Arre, Navarra) from the 12th century, the Paso Honroso Bridge or the Caballeros Bridge over the Órbigo River, (León), where a knight fought for 30 days to win the favour of his beloved; Puente La Reina (Navarra) over the Arga River, etc.

- Stone Crosses: such as the Ligonde cross (Lugo). These carved stone crosses were placed at the crossroads and were used as guides for the pilgrims. They are frequently seen in Galicia and Portugal, although they can also be found in the area of Cantabria and some parts of Castilla-León. In popular Galician mythology, they served as protection against a chance encounter between pilgrims and the Santa Compaña (ghostly procession of the dead).

- Fountains: these are vital for all pilgrims, for example the peculiar Fuente de los Moros de Monjardín, an old water cistern (rainwater tank) with gabled roof and a deep access stairway; the thermal springs in Ourense, known as “As Burgas”, and Fonsagrada fountains (Lugo), the Wine Fountain, near Estella (Navarra), dedicated to pilgrims and built in 1991 by a group of local wineries, and which also includes a fountain with water.

Basic information to do the Camino:

a) www.santiagoturismo.com/camino-de-santiago;

b) www.caminosantiago.org/cpperegrino/comun/inicio.asp

c) www.catedraldesantiago.es